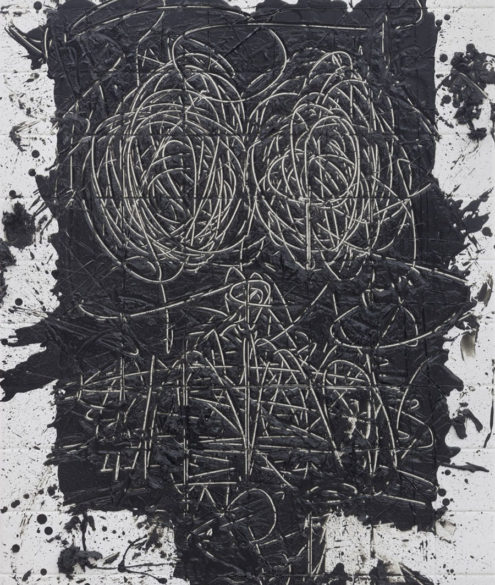

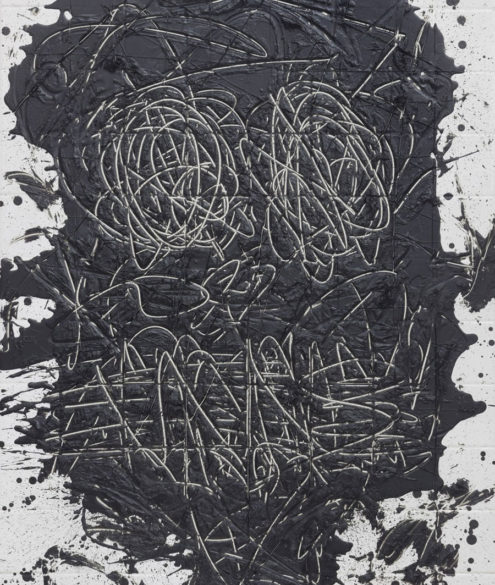

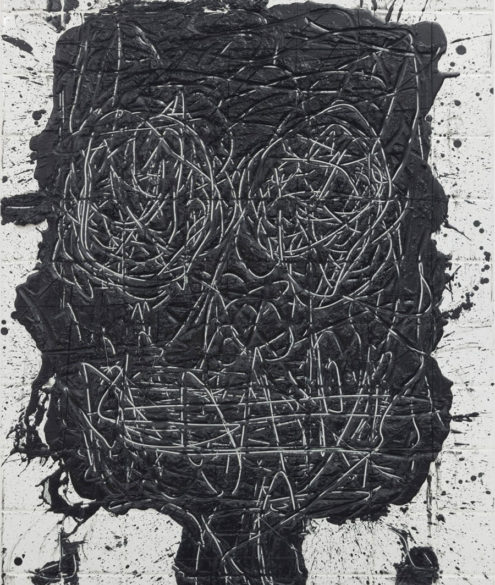

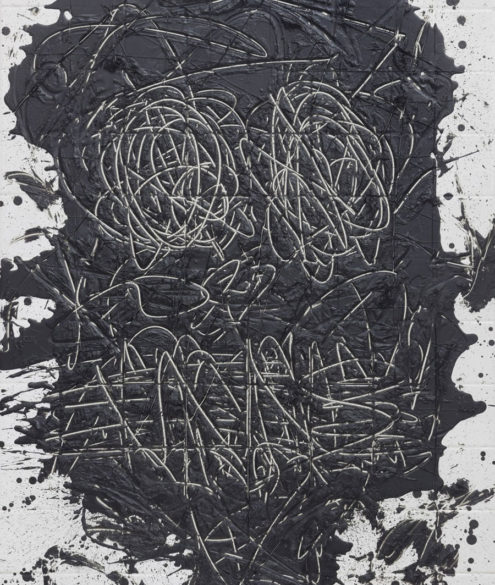

Rashid Johnson, Anxious Men

Re-telling the dark wounds of fear

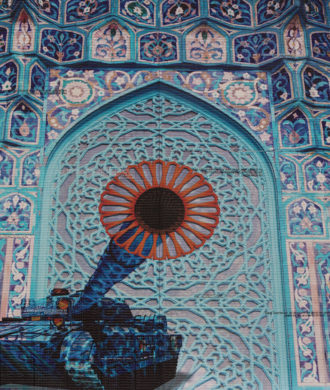

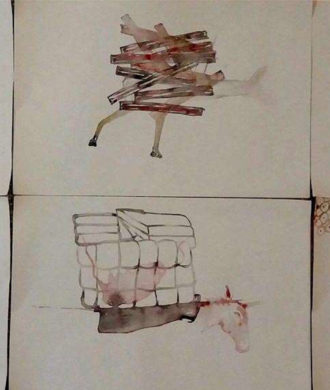

In 2015 The Drawing Center presented Rashid Johnson’s Anxious Men, a site-specific installation created by the artist with curator Claire Gilman for the Drawing Room gallery. The core of the exhibition was a series of black-soap-wax-on-tile portraits that Johnson calls his “Anxious Men”. Executed by digging into a waxy surface, they enacted a kind of drawing through erasure and represented the first time Johnson worked figuratively outside of photography or film, and on such a small scale.

Invoking such varied themes as the black experience in America, the dialogue between abstraction and figuration, and the relationship between art and personal identity. His work is wide-ranging and has been discussed within the context of contemporary painting, photography, sculpture, video, installation, and even performance.

Johnson’s previous work had been more conceptually-oriented, approaching questions of race and political identity. Universally accessible and employing common visual tropes such as the monochrome and the grid, Johnson’s work is also self-referential, making specific allusion to his upbringing in Chicago in the late seventies and eighties and the Afro-centric values of his parents.

In 2016 post a stunning change of guard in the US this series becomes an even more haunting rendition of identity, colour and fear. Each work grittier than the next, channeling the fissures in our minds into devastating effect. Textured with tar-like wax it feels almost like a scream ripped through its body. It is a dark emotion and his art queries, like a tightly wound violent knot, cutting deep across cultures. The relevance of its urgency stark and raw. In ways that shatter the world’s tinted glass Johnson furiously jabs, slits, strikes a story in his unique language. Anxious Men is an important series in not just African American identity and race but in the deep seated psychosis of growing fear, now more so than ever.

Photo: Eric Vogel

Rashid Johnson’s Works across the disciplines of painting, sculpture, photography, and video, exploring his personal past and identity within the larger context of African American intellectual and creative history.

THE SHOW

Included wallpaper depicting a photograph of the artist’s father from the year Johnson was born, and an audio sound track comprised of Melvin Van Peebles’s “Love, That’s America,” a song originally featured in Peebles’s 1970 film Watermelon Man, that was also popular during the occupy wall street movement.

In this way, the exhibition creates an immersive space that implicates not only the artist but also the viewer in its interrogation of selfhood and identity.