Vinu VV – A Very Very big ‘Ocha’

As an artist, Vinu VV shows so much potential with his installation. It has the finesse of a masterful showman. The strategically placed pillars, the spotlit men in a full embrace, the olan man with the foil takeAway container. The screen with the sloppy subtitle font. All are a cog in the visual wheel which the artist maneuvers to take the audience with him into the way he sees the world.

Vinu VV, hails from Kerala. If one grew up in Kerala, then one knows how intertwined caste is to the culture here. Questions like “evidenna? Nair-a?” (where are you from? Are you a Nair?) are questions thrown at one through school, college, fests, etc. If you are not part of the upper caste bubble, then you might have grown up like me in Kerala on a regular diet of stories of abject discrimination and its haunting psychological repercussions on an entire generation. At your neighborhood, at the temple (which was a very integral part of daily life), in ferrying boats or at pedestrian alleyways these questions chase you. It is a very unsettling history of a state that became a breeding ground for strong communist ideologies.

The artist throws light at that same strain of issues that still exist in society. Only Kerala is no longer the cradle of revolutionary communists and social reformers. It is a tourist haven, a rain-soaked-economic-

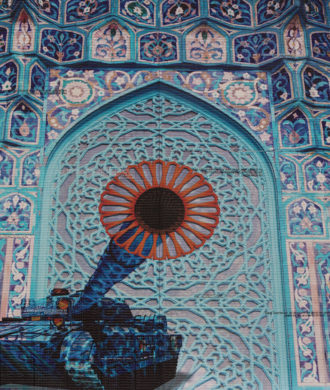

Vinu VV’s installation Ocha (sound) is a site-specific work. It has been perfectly placed deep inside Aspinwall mimicking the skeletons buried in god’s own land, away from the tourist’s camera. One passes a labyrinth of hanging art tapestries and almost crosses over into Vinu VV’s art room. It is then that the art appears unannounced and knocks you out. You are startled at the two pillars bulging with a massacre of silhouettes pinned on nails. Like locusts devouring a tree the sense of discomfort is instant. It is a similar reaction I had as a child visiting Chottanikara Temple where legend has it that the mentally unstable are healed by the divine goddess. Here too my body stopped immediately as it did in the temple, old reflexes came alive, but I forced myself to look-in rather than look-away and take in the raw, rusted brutality of his art. And as the haze clears, the artistry of Vinu’s work shines.

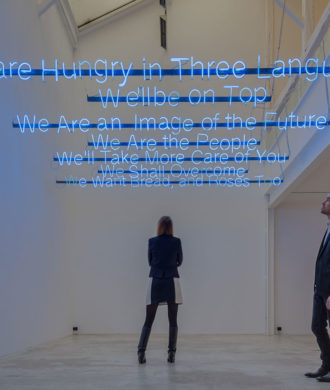

His art to me speaks not just for the Dalits, but for all those in the fringes of the society. He nails each wooden man unclothed, masked, unmasked on long rusted nails as a depiction of the systemic societal crucifixion at large that is at play. Everything has meaning, every element plays its part. He has used the wood from the Odollam tree, also called the suicide tree for its poisonous fruit. A mixtape of Malayalam cinema dialogues based on Malayalam literature runs in subtitles on the side, on a screen.

Almost life-sized sculptures are staged around the room – small, feeble men begging, two in an embrace, one poised behind a charkha – all bring the scene to a point of convergence, to a land where so much has progressed and yet so little has changed. His art has a unique native fervor. The Odollam wood, the hand-carved, unfinished raw-edged sculptures, the sound of literary dialogues speaking of breasts and fields. It all perpetuates the story of a familiar community. But one that is deeply flawed. Boiling in rage, resisting change and sinking in the heap of its own rotting carcass.