Who would be the Turner Prize Winner?

Turner Prize, one of the art world’s most amped-up awards; from Anish Kapoor to Wolfgang Tillmans or Elizabeth Price, Turner has brought them great acclaim and much fanfare. However, the Turner prize has, from the onset, been a subject of heavy criticism. Its nominees, its processes, its selections, all subjugated to scrutiny and generous reproval. The market fortunes that chase the winners of this coveted prize has only somehow added to the speculations. The man who started it all, Sir Alan Bowness, said in one of his interviews to the BBC that the Turner Prize was born out of his enthusiasm for modern art. He goes on to state that the controversies that surround the Turner prize at that point might have actually been a very good thing. It was publicity that got them on the front pages and gave them a marquee focus, in turn growing their influence amongst the urban demographic.

Though the Turner prize has had its ebbs it has also soared as a platform that understood the pulse of the current, cultural tapestry. It was, and continues to be, very ‘now’! And in spite of its fair share of art grumblings, the prize worked as a key catalyst in ushering in a wider appreciation for art, especially contemporary art.

In 2017, I would like to say that the most exciting thing about the Turner prize shortlist is that it includes three remarkable women, increasing the chances for women to claim their space under the bright lights of art-awards-market recognition. But, that would not do justice to the incredible tales all these artists on the shortlist represent through their practice. This year, age, diversity, medium all collude to bring us a fascinating range of artists. We look at their wider oeuvre.

Hurvin Anderson

Large-scale drawings, paintings, photographs, sculptures all form part of his work. His art predominantly deals with social histories and shifting notions of cultural identities. It is a subject that has been core to many artistic pursuits. So what makes Anderson’s work resonate? Hidden landscapes, urban imageries, home scenes, all become emblematic of his perceptions of culture and identity. The grill which features in many of his paintings is a motif that sets the scene for home – Jamaica. The context, space, the motifs, all work in tandem to craft a cultural commentary that is steeped in his personal memories and enquiries. The artist has spoken often in interviews about the impact his visit and residency in Trinidad had on his practice. All those experiences and ruminations have found its way into the iconography and textures of his works adding a unique authenticity to the composition. His art holds a transportive quality to the domestic, everyday life of the Carribean. But they are more than that. The grilled windows instil a sense of in-betweenness – imprisonment, exclusivity, protection, exclusion… These paintings also place the decorative grills in a prime spot instead of in the background, becoming markings of his culture. It is awash with layers that are autobiographical, they keep building his case about black identity, Caribbean identity, migration, the politics of otherness.

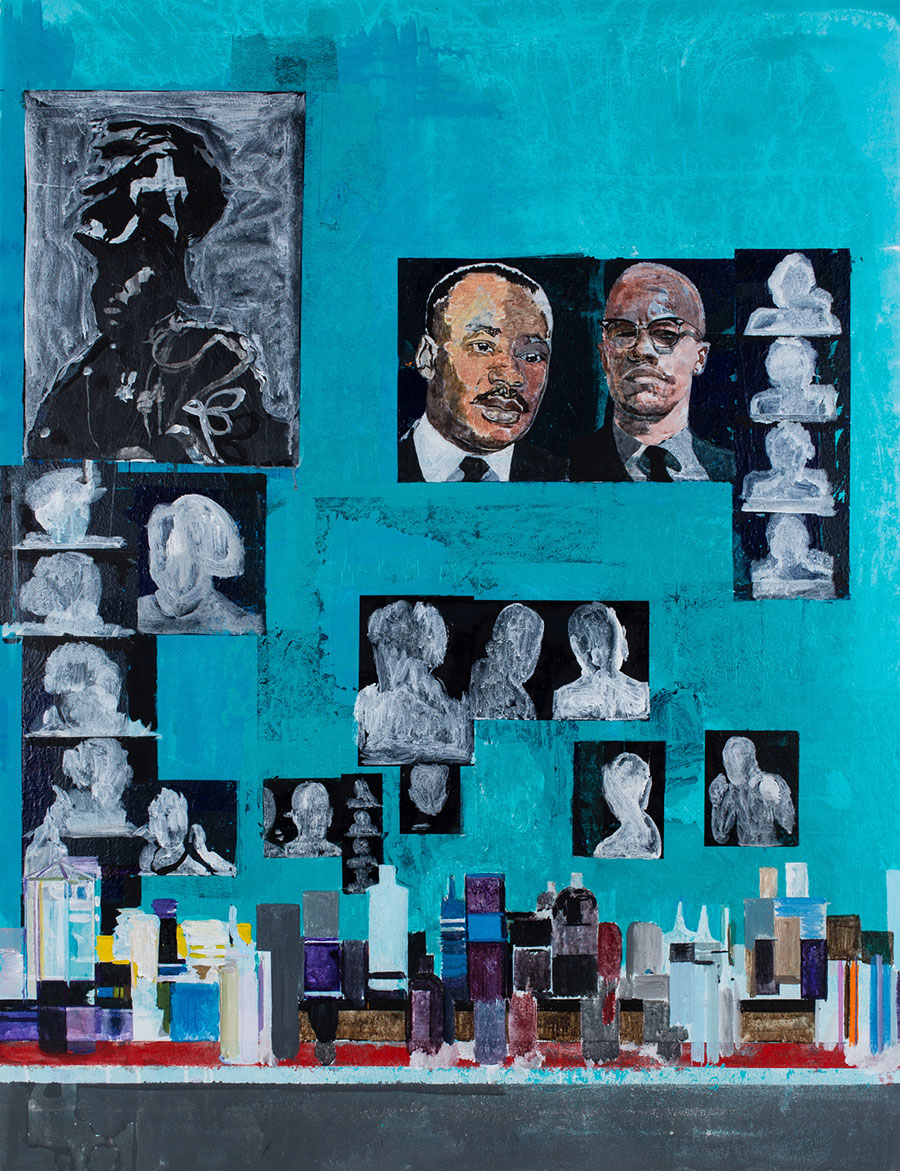

The Barbershop series anchored on the namesake is institutionalised in the Black culture as a haven for men of colour to come together, feel included. The images of legends plastered on the wall stir memories of a personal scrapbook. It is a tight frame that grips your focus. The jaggedness of its imagery perpetuating a wear-and-tear of time on ideology. The white shadows populate the space. What do they imply? A Napoleanesque silhouette, an Ali ready to fight, photobooth strips, fashion shots. They are the moons that lift his heroes. The key players amongst the shadows of a mixed supporting cast.

In Backdrop from the same series one witnesses a space in motion without characters, black hair strewn on the floor, the atmosphere feels alive, it is a scene still in action. It has life, but no figures. The imagery also brings with it a realisation as these havens where people of colour turned to for a feeling of acceptance still exist. The cohabitation of the Barbershop in modern urbanscapes reels you in to ponder and pause at the implications thereof. Anderson is a worthy adversary and in his works, the emotions that soar are very crucial to the ongoing discourses.

click the images for credit details

Rosalind Nashashibi

A Palestinian-English artist based out of Liverpool. her art is very self-aware and unpretentious in its delivery. Nashashibi’s films have a documentary-style feel, sensitising oneself to issues and its realities. Like the work on Gaza wherein, the depiction of school children playing brings an everydayness of life to a troubled land. She called the film Electrical Gaza because she felt the atmosphere was charged with tension, violence, anger.

In Vivian’s Garden made by her for Documenta 14, she charts the life of two artists who are also mother and daughter. The film looks at them, two Swiss-Austrian living in Guatemala, in a sort of self-imposed exile from their country. Guatemala simmers in its own complexities but Nashashibi sets her eye within the confines of the artists home. The revelations are incidental.

In her interview with Hull, she speaks about looking at subjects closely, focussing intimately at enclosed situations or encounters, and in that limited space she explores wider archetypes which guide a humanitarian commentary, often touching a raw nerve along the way. She also uses animated objects, making the frames break like a pause, to refocus and in ways, it gives her narrative an almost surreal feel. Nashashibi is a daring artist, her art takes on strong subjects and amplifies its concerns in a manner that is almost poetic and immersive. She shoots in 16mm – the film format with a cult following. Sought after even now by documentary and art filmmakers for it lends their work an old-world approachability; an honest, unbleached, organic experience. Nashashibi’s art is loud in its anthropological observations but it is unassumingly simplistic in its format, and as many critics state, profound in its delivery.

click the images for credit details

Lubaina Himid

Her art celebrates Black creativity, its history, its people while consistently challenging the institutional invisibility of their contributions. Himid’s inquisitions tackle the imbalance in the way history continues to be chronicled. Her repertoire is her advocacy of the right recitation of the past and the present. Spanning ceramic antiquities to Guardian newspapers, her art represents the steady embargo on Black narratives. Going through her career graph one gets a sense of her empowering voice. It is a voice that has grown bigger and stronger over the years.

Looking back, Lubaina Himid has balanced an impressive practice as an artist while also being an exhibitor and curator of critically acclaimed group shows. It is a rich exchange that she has with her world of art. The oldest artist on the shortlist at 62, she makes paintings, prints, drawings and installations. Her art might unspool the events in history, culture, development wherein the contribution by people of colour has been woven out and demand its re-integration but it is masked with wit and satire and served with ingenuity.

Her paternal roots are in Zanzibar from where she shifted to Blackpool due to the untimely death of her father. Her English mother, a textile designer, shifted to London soon thereafter. Growing up, she has spoken, in interviews, of being asked about her identity and colour. Where did she belong? Questions that shaped her artistic viewpoints as she embraced the world of art.

click the images for credit details

Himid started her career with theatre design before becoming an artist. She infused the mechanics of drama and storytelling that theatre choreographs so brilliantly, into her exhibitions. She has often reiterated in her interviews that her work is about having conversations with other people. It unravels a story that actively engages with the viewer. In Naming The Money, the artist is referencing European art which depicts scenes of aristocracy where the black slave is seen quietly playing their part on the fringes. This installation became her assemblage of all those silenced characters. A striking installation of larger-than-life-sized Black characters, propped-up – each named, each with a backstory, each ready to participate with you as you walk in their midst. It is art that is well orchestrated, upholding its nuanced integrities as each character adds their voices to that history. Here, the artist appropriates and interrogates European painters and combines aspects of her African heritage to question the role of visual power.

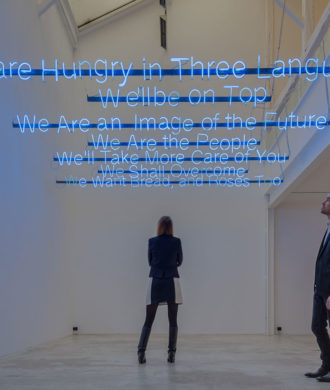

In Himid’s Swallow Hard: The Lancaster Dinner Service, as the communication reads, “It is an intervention, a mapping and an excavation”. She bought patterned plates, jugs and tureens and experimented by painting over them. It remembers slave servants, sugary food, mahogany furniture, greedy families, tobacco and cotton fabrics, but then mixes them with British wildflowers, elegant architecture and African patterns. In her other work, Negative Positives / Guardian Paperworks she takes the Guardian newspaper featuring black people. She colour blocks areas with African patterns, curating the space around the black person’s image to examine the portrayal of Black lives in newspapers. It is news re-imagined and styled to place the spotlight on the Black person on the paper, forcing us to better understand the institutionalised narrative approach to Black people and their stories in media. Her art forces you to discuss and acknowledge that contribution, to add its rightful imprint to history. Her art is trying to make the narrative whole, make the narrative of history harmonious by acknowledging the diversity that lived it. From exhibiting under-represented black artists, especially the black women artists, to creating discussions on important issues through her intensely evolving practice, Himid is a leading figure in the British Black Art Movement.

Andrea Büttner

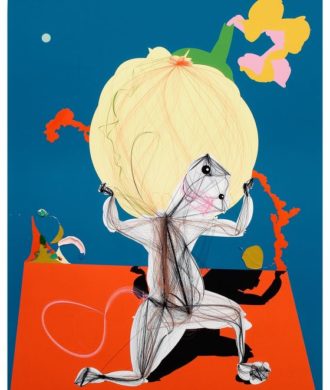

She works with woodcuts, but her portfolio spans to textile, photographs, films, sculptures etc. She mines ideas of faith from her own life and introspections. But it is abundantly enriched by her background in research. Her art is disconcerting but not in the lineage of shock-and-awe but more in terms of its measured visual simplicity juxtaposed with a very sagacious integrity to subjects close to her. Her film Little Works was collaborative work with nuns. As the convent had strict rules, Büttner was not allowed to film inside, so she gave the camera to the nuns to film their lives. It is a short film offering a genteel slice of their life. The film shows us their art and craft, their easy banter and tender engagements within this peaceful, idyllic community. It is an appealing life away from the plastic intricacies of modern life. But, the context of the film within the boundaries of a strict convent, its heavily conservative doctrines, all steam up to the ambivalence that defines many of our spiritual and faith-based customs. She delves into these parallels, it is an element she handles with decided comfort through her art.

click the images for credit details

Büttner stretches the subject of faith and connects the dots to life and visual culture to make interesting constellations. Her art is multi-pronged. She comments on issues of socio-political concerns, capturing the dichotomies in religion and even weaving in special nods to other artists and art practices. Büttner’s work also sparks confrontations about aesthetics in art. It is a lot to lay into one’s art but she does it with a heightened sensitivity to materiality synchronised with symbolism. In her conversations with Lars Bang Larsen at Collezione Maramotti, when asked about her fascination to woodcuts with pop art and Andy Warhol she reveals, “Andy Warhol was queer, he went to church all his life. He lived in an utterly catholic family, with his mum. But I became interested in him because of his Screen Tests because his work deals a lot with shame. Then there is another relationship… between pop art and woodcuts. I tend to show the woodcuts together with the screenprints to mark that the woodcutting is the first pop medium. It came up in the middle ages to popularise imagery. It is the first medium of mass-produced imagery. So different connections to pop. But maybe my dearest (connection) is Andy Warhol’s queerness.” Her PhD was on the subject of Shame and with her own experiences with faith, all these conspire to create a tapestry of intersecting tales. Shame, nakedness, virtue, morality, aesthetics, spirituality all come together to drive expanding discourses in her art to reflect an inquisitive and informed artist.

Turner prize has turned out aces this time around. Does their art have the shiny, glitzy, sensationalism or the confusion of lights going on and off or the titillation of playing with newer materiality and mediums? Should that even be a criterion? We hope not. So who is our favourite? It is a very difficult pick and my personal favourites are Himid and Büttner. But whoever it may be Turner Prize would admit an artist they can be especially proud of as their winner this year.